Your behavioral biases could cost you hundreds of thousands of dollars in portfolio returns over its lifetime. I’m going to show you approaches to making preferable investment decisions you can use right now. Simply put: if you hate losing money, you’ll love this post. Let’s get started.

Behavioral finance acknowledges that you and I aren’t rational, logical, or well-informed. We take tips from friends, hate losing a dollar more than winning one, and don’t internalize new information.

The nation’s leading investor behavior study for over 25 years, DALBAR, said mutual fund investors earn less than market indices suggest while this says average investors earned 2.6% annually while U.S. stocks returned 10.2%.

What’s a Behavioral Bias (aka Cognitive Bias)?

A behavioral bias, or cognitive bias, is forming opinions that are based on inaccurate information, lack of objectivity, and stray from rational thought.

Behavioral biases form out of your life experiences. These biases affect the decisions you make every day – including financial ones. Here are eight behavioral investing mistakes that will cost you money.

1. Memory Bias

Translation: Things will be different this time.

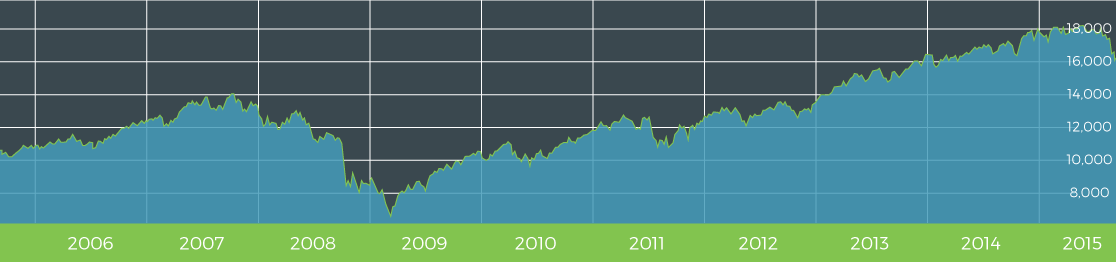

Your recent experiences weigh more heavily in your planning and decision making than your past experiences. How many people do you know who pulled their money out of the stock market in 2009 because it tanked in 2008?

Unfortunately, they missed out on the subsequent 50% rebound for the rest of the year, assuming they pulled out at rock bottom. These may have been folks with solid investing plans who were aware that the market historically returned between 7-11% but still couldn’t see past that 50% drop.

Loss aversion means it's better to not lose money than to win it.

Tweet ThisInvestors suffering from loss aversion fall into this category – the fear of losing money outweighs the potential for long-term gains.

Similarly, people are surprised that the companies who tend to do well one year, do poorly the next, and vice versa. As Investopedia points out, however, this makes sense. If a stock did well one year, it might have set high expectations and a big price tag.

To match that, it would have to outperform its previous outperformance, which is challenging. Past performance isn’t an indicator of future results.

2. Recency Bias

Translation: It’s always been/will always be like this.

Concluding recent events will continue into the future. Remembering things that happened recently with greater clarity than things that happened a while ago.

For example, if you started investing in 2008, you probably thought the stock market was awful with no end in sight. People panic under these circumstances and sell.

Historically, the market has had a 7% average annual return. However, because there was a ~50% market dip, investors saw the market low lasting forever.

On the other hand, if you jumped into the stock market after the bottom of ’09, you probably thought it was the greatest thing ever as your investments tripled. You need to look at broad trends and not get excited over the small ones.

The market always goes up.

Get our best strategies, tools, and support sent straight to your inbox.

3. Overconfidence

Translation: Indexing is for people who can’t do it on their own.

You’ve got this investing thing nailed! You bought Tesla at $100 and were mining Bitcoins in 2011. It’s the same reason you’re better than the average driver! People should give you their money to invest.

Two reasons why this behavioral mistake is dangerous:

- You’re ignoring sample size (or broader market trends)

- You’re claiming long-term index-based investing is inferior to stock-picking.

Two good picks don’t make you Warren Buffett and index-based investing is the best strategy for the majority of individual investors.

This Dilbert comic sums it up perfectly. People who trade a lot frequently make this mistake.

4. Confirmation Bias

Translation: This fact backs me up so I’ll ignore the one that doesn’t.

You’re too slow to change your beliefs to match new evidence and primarily look for evidence that supports what you already believe. Personally, if I were to learn baby tears powered Google’s search engine (they don’t), it would still take me a while to toss their stock.

I admire the company and have done well with the stock, not to mention they’re on my list of companies I wish I had bought years ago. Some of my friends work there and casually mention the perks I wish I had.

Given their slogan of “Don’t be evil,” news like that would likely kill their stock, and I’d take some severe losses because I wouldn’t react quickly enough.

5. Framing

Translation: Is the glass half-full or half-empty? It’s better to look at what you’ll gain vs. what you’ll lose.

We suck at answering the same question consistently when the questioner changes the framing on us. Check out the below study on this phenomenon:

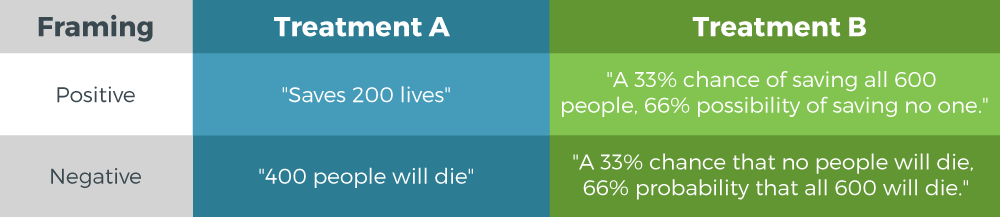

Participants were asked to choose between two treatments for 600 people affected by a deadly disease. Treatment A was predicted to result in 400 deaths, whereas treatment B had a 33% chance that no one would die but a 66% chance that everyone would die.

They presented the choice to participants with either a positive framing, i.e., how many people would live or, with a negative framing, i.e., how many people would die.

Treatment A was chosen by 72% of participants when it was presented with positive framing (“saves 200 lives”), dropping to only 22% when the same choice was presented with negative framing (“400 people will die”).

6. Mental Accounting

Translation: I don’t want to lose my kid’s college fund.

Mental accounting is a subset of framing. You separate your decisions based on the purpose of the investment as opposed to looking at your overall picture. Do you have investments for education that are allocated differently than your general portfolio with the same time frame?

If you are assuming two investments have the same time frame, determine how you’re going to invest. It shouldn’t matter what purpose you plan to use the money for.

Another aspect of this is the house money effect or, taking bigger bets once you’re up. I certainly fall into this trap every time I play poker. Once I’m not risking my money, what’s the harm in losing the house money?

It does make sense to do some mental accounting when you have different time frames (money to buy a house in two years vs. retiring in 30).

7. Regret Avoidance

Translation: It has to come back up some time, right?

Losing money sucks when you make the wrong choice. It’s even worse when it was a risky decision with the potential for high rewards.

This behavioral mistake happens all the time in investing because no one knows what’s going to happen next. If people knew, you’d know their name because they’d own everything.

However, it’s often better to bite the bullet and leave a sinking ship than to go down with it. Why?

Because no one wants to admit having made the wrong call.

What I try to do is offset my regret with this behavioral investing mistake by enjoying the fact that those losses will mean some sweet tax reductions in the future.

8. Affect Bias

Translation: I like their mission.

Companies that make you feel good or wish you worked there (e.g., Google), tend to do better than companies that make you feel like they’re part of an evil corporate empire. In my case, the company that would have been an exceptional choice to have in my portfolio, but I avoided, was Exxon.

I felt that I couldn’t buy their stock because I studied environmental science and feel like I understand a lot of the issues caused by oil drilling and consumption.

Up until this point, it turned out I made a good call because oil slumped, but if we ignore the small sample size (2 years) and my strong bias against an energy producer, it could have been a solid part of my portfolio.

In this case, I feel as though it comes down to making a conscious decision. I didn’t buy energy companies knowing that I would likely take a hit to my portfolio, but often these kinds of thoughts creep in unconsciously, and you need to be careful of them.

Behavioral Investing Mistakes: What Does It All Mean?

It means that investment mistakes can be reduced (or avoided) if you know the signs. Awareness improves performance.

Made repeatedly, these biases can have a negative impact on investment performance, especially when going down the route of buying high and selling low. Think, be conscious of what’s going into your decisions, and you will be fine.

Featured Image Photo Credit: “Head in Hands” by Alex Promios on Flickr